You wouldn’t think a one-armed man could shinny nine stories up an elevator cable, especially a sixty-six-year-old man. Then reach over with his left foot to release the emergency lever opening the door onto the ninth floor and spring like a spider to land on all fours inside. It helped that he weighed only 136 pounds and was long-legged

Peter imagined that he’d leapt onto the movie set of a film about life in normal times. The office space, flooded with dawn light pouring in floor-to-ceiling windows, gleamed as if brand new (although likely forty years old), free of the thick, acrid dust coating everything exposed to the sky outside. It remained in the pristine condition it had been in when abruptly abandoned years before. Computers sat on desks in dozens of cubicles, jackets remained hanging on hooks, food wrappers scattered over common tables, their contents long since devoured by rats, as if the occupants had vanished instantaneously. Sucked into the ether, some said to explain such instant vacating in L.A. and other cities. “Rebalancing,” they said.

Mysterious forces reclaiming the planet.

What these forces were exactly was unknown. Survivors from normal times said heat, drought, famine and fear drove people out. Nature did. But wouldn’t that have happened over many years? Why would they flee all at once? Perhaps sirens wailed through L.A., warning of an imminent nuclear attack? This happened often in the old days, when everyone wanted to destroy everyone else and claim the meager resources remaining to the planet for themselves.

Peter remembered those times well. The Ruskies, red Chinese, North Korea, and the Iranians all

waving fists at the West, which waved back, spoiling for a fight. Or perhaps occupants learned that someone in the building was infected with SARS-MINK16. A single case could imperil hundreds. It was estimated that MINK16 had wiped out one-third of the human population.

Peter envisioned escapees jamming stairwells as they had in the Twin Towers bombing sixty

years before, their crushed bodies left to decay where they fell. Others fled to the roof and leapt

off. Better to die quickly than have your lungs fill with mucousy cement that glued tissues

together and suffocated you. Bones of the long-since dead lay in heaps at bottom of stairwells in

some buildings or sidewalks out front. No one dared enter such places since the virus remained

dormant in dead tissue for years.

—

There’s days you can’t walk out on the street downtown, where heat is trapped in building canyons. Melting asphalt catches hold of your shoe heels and pulls shoes right off your feet. Happened to me once. I stepped barefoot into liquid tar and scalded skin off the sole of my left foot. Wasn’t much use then: a one-armed man hopping around one-legged. Couldn’t scrape the tar off until the skin healed beneath.

Days when it reaches one hundred twenty degrees in the canyons, you hole up in abandoned buildings by day and scavenge for food and water at night, what little there is left. Find you a room empty of two-legged rats and enforcers and barricade it best you can. Like I done on the third floor of Oakley Tower. Spend my days sleeping and sweating and playing solitaire with a deck of cards I found, knowing there’s people in that building will slit your throat for a bottle of water. Or a block captain who will force you to join his crew. They rule with an iron fist like all dictators. Got no tolerance for single walkers like me. Join up or get out. Don’t want them to catch you in the stairwell. So I got skilled at climbing elevator cables, going up through the hatch on a stranded ground floor car, crawling up like a caterpillar, gripping the braided cable with my feet, reaching up with my left hand and inching upward. Plenty of friction for my hand and feet to catch hold of. I excelled at rope climbing in basic training before they sent me to Afghanistan. Drill sergeant said I was half monkey. Didn’t know it then, but I was training less for the Kush than the life to come later. Black as the holes of hell in those shafts, but I found a laser penlight I clutch in my teeth. Leave the elevator door open up top and crawl up toward the lit opening like a moth attracted to light.

Couldn’t climb cable after I scalded my foot, which I wrapped in a rag. So I’d listen at bottom of the stairs. After deciding it was safe, would hop up step by step. One day I opened the door onto the third floor and there’s three men standing there. Bad news. Gray dots formed crescent moons on their foreheads. Looked in the dim light like they was branded by a lit cigarette. Two of them huge and ugly as wolverines. The third a runt, but you knew he was boss. Would cut his mother’s heart out and eat it if he was hungry enough. I ain’t seen such meanness in a face since Uncle Harley when I was a kid. Spent his time in the Liberty Corps down on the border, hunting refugees. Looked like Harley, too, in a smaller version.

“Look what we got here!” he said. “A one-armed bandit. Looks like you have only one

good foot, too, boy.” Flat pissed me off him calling me “boy,” and me thirty years his senior.

They laughed like I was a community joke. “What you doing in my building, pops? We knew

you were here. We’ve been looking for you, but can’t figure how you get in and out. What

room are you in?”

Didn’t dare tell him. “Wherever I find an empty,” I said. He studied me, dubious like.

But they couldn’t kick down every door in the building to look: too many of them and too hot.

“We call you ‘the one-armed spook.’” He grinned—you want to call it a grin. His teeth filed to sharp points. “How did you lose your arm there, gramps?”

“Lost it in the war.”

“NATO or Iran?” he asked.

“Afghanistan. Before you was born.”

“My old man fought in Afghanistan,” he told his cronies. “Bastard left and never came back.” He got up in my face and held a blade to my throat. Its tip dug in. “I’m going to tell you once, pops. Join up. Pay up. Or get out. I won’t have any freeloaders or single walkers in my building. Losers who fought in Afghanistan leave a bad taste in my mouth.”

One of his lieutenants kicked my foot. “Or die!” he barked. Pain throbbed up my leg; I fell hard against the wall. Gave them another good laugh.

“You’ve got until tomorrow morning, same time, same place. Join up, pay up, or die.

I’m feeling generous today or else I’d toss you out a window. Be here, pops!”

Disaster brings out the worst and best in people I learned in Afghanistan. There was some boys stuffed gas-soaked rags in the mouths of captured hajis and lit them afire. Others dropped to their knees and gave a dying enemy mouth-to-mouth. Nowadays, you want to survive out here, you got to separate the wheat from the chaff.

I hung out in a nearby office building parking lot until my foot healed, not daring return to my pad. Tiptoed past dried bones stacked one side of the lobby—victims of SARS-MINK16 likely—hoping not to wake the virus. Made my way downstairs into the parking structure. Most dangerous place you can be, but the coolest. Scalpers hang out underground. Some say they’re cannibals. Their genetically modified dogs hunt with them, red-eyed and vicious, like dire wolves. I don’t believe all of it, but you can’t be sure anymore. I hoped bones in the lobby would keep them away. Sometimes, lying there in the dark on the lukewarm pavement, hungry and thirsty, I heard stirrings. Rats, I hoped. If one got close, I’d catch and eat it. Good news was that tar kept my foot from festering. A week below ground and I was good to go.

—

Los Angeles held out longer than most cities. When it went down, it went down hard. Local government collapsed, along with the power grid, water works, schools, first responders, medical care, grocery stores and pharmacies…all the fundaments of civilization. And the unity of purpose it was built upon. Houses and apartment buildings, downtown office towers, and movie lots were abandoned as people fled the heat and chaos. No food but what remained in shuttered stores and houses, soon cleaned out. No water but what remained in pipes and toilets in that time of forever drought. The glitziest district downtown near the convention center, where gleaming skyscrapers went up in the Twenties, was dead quiet. Glass-sheathed towers reflected merciless sunlight. Pershing Square, once full of tourists, was deserted, its trees leafless snags. A homeless camp that once covered the square was abandoned in the mid-Fifties.

Too hot to support life. Someone had scrawled “Welcome to Beverley’s Asshole” across a huge, dark digital display panel on one high rise. No one occupied the empty buildings, given heaps of tainted bones in their lobbies. Moreover, sunlight pouring through glass walls made it one hundred fifty degrees inside when it was one hundred outside. Survivors feared the skyscrapers would be toppled by an earthquake or fierce, parching Santa Ana winds. They took refuge in older parts of downtown where buildings were lower. How, they wondered, could city officials in normal times have been such fools as to believe their gentrified metropolis was out of nature’s reach.

Downtown condos, abandoned in the mid-Fifties, had become havens for the dispossessed, who poured in from all over hungry America, their campers and RVs—useless now without fuel—parked higgledy-piggledy in the streets below. Though fully furnished, apartments were so hot the new residents had to break out the windows. Flat rooftops, the finest real estate in town, were commandeered by clans and cartels, sealed off from stairwells by thick steel doors. They were washed by breezes off the ocean five miles away, the air fresher and cooler up there. Roof dwellers lived under thick, insulated canopies. Solar panels provided electricity for refrigeration and A.C. units that were readily available in the abandoned city.

They grew shade trees in huge planter boxes. Palm trees and palmettos sprouted voluntarily in pockets of soil. Flocks of parrots flew from rooftop to rooftop; their raucous cries echoed through canyons below. Roof-toppers grew gardens in raised beds and lined walls of the rooms directly below with stucco to waterproof and use them as cisterns to store water from atmospheric rivers that occasionally drenched the drought-stricken city. It was a dangerous business. Too much weight could collapse a building, as had happened to a tower on Third Street: one floor crashing into the one below with ever-increasing momentum, gutting the building and killing everyone inside, leaving behind a pile of rubble eighty feet high. Then the rain stopped altogether. No more atmospheric rivers to fill cisterns. No more gardens. Five years now without a drop. Survivors hacked into old water lines in search of civilization’s fossil water. Most were forced to abandon the city.

Early on, the Patriot Patrol and Night Walkers assaulted homeless camps and beat the inhabitants to death in their sleep. The Feds sent patrols to capture the able-bodied and sent them off to fight in Iran or on the Eastern Front. The homeless formed governments and security patrols to protect themselves. The mentally ill among them became sane, the ne’er do wells enterprising.

Nature saw its opportunity, and vines crept up buildings—ivy, bougainvillea, dawn flower, and honeysuckle—crawled in doors and windows and formed a carpet over floors, spilled off balconies in green cascades. The former headquarters of the Writers Guild of America was covered by Black-eyed Susan that made the building glow bright yellow at sunset.

Century City was slowly buried under vegetation. Skunks made dens in hospital wards, possum favored crawl spaces under houses, raccoons liked living rooms, rats loved mattresses.

Occasionally, a settler spotted a mountain lion perched atop a roof. Packs of coyotes feasted on feral cats, dogs, and human babies, it was said. Owls hooted at night under a star-filled sky. The city that had always yearned to be exotic was becoming Palanque, a Mayan ruin covered by jungle.

Oil seeped up from underground as if the Mesozoic era was making a comeback. Back in the Thirties and Forties, there had been talk of collecting rain water from atmospheric rivers in

cisterns, and settling ponds so it could percolate into the huge, dry aquifer underlying the city, but contractors and homeowners’ groups vigorously opposed it, so nothing was done. Rain that might have saved the city continued to be flushed down the Los Angeles River out to sea.

—

One morning, I climb up to my pad with bags of chips, nuts and candy bars I busted out of a vending machine on the ninth floor of a building on Spring Street. Fucking gold mine. When I swing out of the elevator shaft, there’s a lady sitting on the bed I made of plastic garbage

bags stuffed with rags, drinking a can of warm beer from my stash. Maybe four-feet-five, thin as a pencil, shiny black hair falling to her waist. Only her head normal size. Still, about as beautiful a woman as I ever seen in skinny miniature. I stand staring.

“Who are you?” she asks.

“No ma’am! Question is: Who are you? How’d you get in my pad?” Then I see the door is tore off its hinges. “That’s gotta be the captain’s doing. Isn’t no way you could bust down that door.” Although you hear about people with special powers that they couldn’t survive

without. Me, for instance. Biceps on my left arm as fat as most people’s thighs, my wrist and hand half again normal size. Maybe she’s one of us.

She shrugs. “I have as much right to be here as you do. Ownership is over.”

“Your captain don’t think so. He owns you, too, don’t he? His enforcers use you any way they like. He send you here to bait me?” She shakes her head no, but her eyes blink yes. I check back rooms for unwanted guests. They tore the place up good, maybe looking for evidence that I live here. I tell her she better leave before I nail the door back up and reinforce it with two-by-fours I tore out of a wall. She shakes her head, no. When I turn around after

reinforcing the door, she sits bare naked on my bed.

I wave my hands before my face. “What the hell?”

“It’s stifling hot in here,” she says.

“You better get y’rself dressed. I can’t trust myself with a naked woman, long as I’ve been without. You hungry? I figure we have time to eat before they get back. I found Fat City this morning.” I can see she’s wondering what I want in exchange. She gets dressed and we eat.

Like we all do whenever we get the chance. Then someone is pounding on the door. “You in

there, Calamity, and that one-armed freak?” the captain shouts in a hoarse voice.

She grabs my arm. “Rusty will kill you. He thinks he owns me.”

“Captain’s name is Rusty? That’s my boy’s name.”

They try to kick down the door. We throw as many provisions as we can carry in my backpack and a pillowcase. “You got to wrap your arms around my neck and grip my waist with your legs,” I whisper. “I’ll ease us down slow.” Last thing I see is a boot coming through the door. Hard part is leaping over to grip hold of the cable with all that weight on my back. I about take out the family jewels catching that cable crotch-first to soften the landing. Barely get hold with my feet and hand, woozy weak as you get slamming your nuts. I hold on, but Calamity nearly loses her grip with the impact. Right then I could use another arm to catch hold of her. Worries me a second she might live up to her name and fall.

When we land atop the elevator car, my palm is bleeding good. The frayed cable tore it up with all the weight. Captain Rusty and his men shout through rooms above us, smashing things. We go down through the elevator hatch and run outside into a sauna bath. It’s like a fist knocks the breath out of you. At first, you do the woozy waddle walk in heat like that, like walking through a swamp. I wonder how we’ll make a quarter mile when just putting one foot in front of the other is exhausting. Inside, you’re shaded and insulated by rooms around you. “Passive hot.” Out here in the building canyons it’s “active hot.” The sun is a blast furnace. Gives me an idea. I firm my hand against a marble wall hot as a stove top, can hear blood sizzling against it and cry out. It cauterizes the wound, anyway. Stops the bleeding. We have to cross to the shady side of the street. When we start across, Calamity says it’s better to tiptoe over molten asphalt than walk flat-footed. And I know I’ve found myself a survivor.

You go by day if you want to make sure no one follows. Not a whisper of wind, passing voices or cars. No birdsong in that white heat. No droning planes in the distance. They say you can hear waves wash onto Venice Beach five miles west from the rooftops. Down here in the canyons, I hear the city’s ghosts: jumpy beat of hip hop from a car passing long ago, fleeting footsteps, a clatter of voices. It’s one time I heard construction workers yelling to each other in Español from the superstructure of a building overhead. Ghost voices. All sounds are ghostly now, lingering in the thick air long after their source has passed.

The spider logo on the building’s glass front doors is better security than any lock. No intruder in their right mind would enter a spider’s lair. Don’t know what that says about me. Calamity nods at the spying eye of a CCTV cam high up in a corner and regards me in alarm.

“They’re watching,” she whispers. There’s all the technology you want remaining from normal

times if you know how to use it. No grid anymore, no infrastructure except what people rig for

themselves. The spider clan is known for it.

“They’ve gotten used to me. I’m safe here if they let me stay. Maybe ain’t worried about

a one-armed settler. Maybe using me as test.”

“A test for what?”

“Could be we’ll find out.”

“I don’t like it here. It’s spooky.”

Through huge windows looking onto the street, I see three men on a corner down the block, two huge, one short, looking about to see where we went. Captain Rusty and his goons?

I hurry Calamity across the lobby into the stalled elevator car and boost her up through the hatch, then pull myself up atop the car. Trying to figure out how to get her up to the ninth floor, I forget to close the hatch behind us. “I can climb cable, but I’ll have to rig a way to bring you up. I’ll go up first and send you down a chairlift.” She regards me like I’m nuts, looking forlornly up the shaft to where it vanishes in darkness.

I’m maybe half way up when I hear muted voices in the lobby. Then directly below in

the elevator car. A hoarse voice says, “What the fuck’s this? Hatch is open.”

“Someone’s up there,” another says.

We’ve bought it. They’re sure to boost up and take a look. Nab Calamity and see me

hanging from the cable, silhouetted against hazy light spilling out the open door on the ninth floor above. I hope it’s Spiders. Scalpers would be even worse news than Rusty. The hatch goes dark; someone’s head and shoulders come up through. My hand stings like a bastard from gripping the cable. It was okay as long as I kept climbing. I’m afraid I’ll fall. Might be best: crush the SOB’s head. When a match lights up the interior of the shaft, Calamity is gone.

“No one here,” A voice echoes.

Then they’re gone. Maybe upstairs to the roof. Maybe back outside. They didn’t see me hanging there, anyway. Shining the penlight, gripped in my teeth, down at the roof of the car, I see Calamity step out of the shadows. What the hell! “Close the hatch,” I whisper call to her.

My hand throbbing, I make it to the top. Collect jackets left behind, grip them in my teeth and tear them apart, knot pieces together in a rope with my feet and hand, and tie it around a chair. Lower it down to her. “Straddle it,” I call. “Grip hold of the rope. I’ll inch you up.” I wind the rope around my chest and walk backwards nine stories until she reaches the top. It helps that she weighs no more than a twelve year old girl.

“Piece of cake.” I grin, “How’d you disappear like that?”

“I’m small. I hid behind some cables.”

“Was it Rusty?”

“I couldn’t see, but it smelled like him.”

“We’re safe up here. Nobody can reach us. I believe there’s a Spider colony on the roof. You got to be part of their clan to roost up there. I’m a single walker. My philosophy is you can’t trust nobody. Half the time you can’t even trust yourself.”

“I wouldn’t want to be you,” she says.

“There’s times I don’t either. Still, I doubt they’ll bother us none. Might be a protection

to have them there. They marked the building as theirs. Likely why the captain and his pals skedaddled. We have water from what remains in pipes above us, metallic tasting but clean. Plus toilets.”

Unlikely as it seems, we spend a sweaty hot afternoon of sex. Calamity’s as hungry as I am. These days, you take pleasure where you find it. Afterwards, we swap stories. I do mostly. It ain’t often you get a chance to talk to somebody. I’ve nearly forgot how. Once I start, I can’t stop. It’s another thing about these times: you don’t have to make nothing up. Likely, you already lived it.

Tell her how I didn’t return to my wife and kid in San Diego after the war. Wasn’t no use to them single-handed. Or up to Kirby Farm neither, where mother is got Jesus hung on the cross in every room watching you. Besides, my brain was fried from all the ugliness I seen over there. I was worried it turned me ugly. Didn’t want my boy growing up with that. Knew right off I’d wind up on the street. Who’d hire a one-armed man with a scrambled brain? “Maybe I’ll become a one-armed brain surgeon,” I told my mate at the hospital in Germany. That poor boy lost both his legs, so I didn’t have nothin’ to complain about. You learn to laugh about it.

“I lived up in Reinhardt Park East of Oakland until the Oakland Hills fire run us out and burned up the east side of town in Twenty-Seven. Then lived on the street in San Francisco, until cops and the Liberty Patrol beat some of us half to death one night. Let me go when I told them I was a vet and showed them my stump. I felt guilty leaving the others, but you realize we all gonna feel guilty about something anymore. I wound up in Forest Park in Portland for ten years. Safer from fire. We had ourselves a community in the mossy woods. Armed to the teeth, so police and householders left us alone. What they call ‘extra-tropical hurricanes’ drove us out. Huge old Hemlock, Doug fir, and Cedar falling all sides in one hundred mile per hour winds.

“I been pillar to post ever since. Lost track of how long. I slept with women and slept with men. Would have slept with dogs sometimes. I’ve ate dog and rat. Gone hungry more times than belly-full. Killed a man in Oakland once who I caught robbing my camp. He come at me with a blade and I took him down with a axe. Made my way to L.A. ‘cause I heard you could get y’rself an abandoned mansion in Beverly Hills. I did, too. Fifteen thousand square feet and a swimming pool that went stagnant and begun to stink and breed malaria mosquitoes what come over from Africa. I must’ve caught the fever. I still get chills, even on hot days. But stalkers and refugees will kill you for a house. It’s safer on the street among tent dwellers, where nobody wants to take nothing from you since you don’t have nothing to take.”

“Did you kill people in Afghanistan?”

“No, ma’am. I shot over their heads. Didn’t have nothing against them. It’s their country; they can run it any way they like.”

“I killed a man once,” she said. “He wanted me to. His stomach was rotting from cancer.”

“That don’t count. That’s a kindness.”

Besides that, she didn’t say much about her life, except, “I don’t know yet. It’s not finished.”

—

Enough food in vending machines to last us a month. Sugar carbs mostly. More in vending machines on other floors. Peanuts for protein. Greens and fruit is hard to come by. There’s prickly pear cactus if you know how to prepare it. You see plenty survivors hobbling along with the scurvy. Poor bastards. Like we’re on a old time sea voyage on dry land. I get vitamin C from multi-vitamins I find in looted drug stores. Most dumb damn fools lack sense to know we need vitamins. All of it left back in my third floor stash. I figure we can grow veggies up here. Bed them down inside desk drawers under the windows if we can find soil. Regular hot house up here. I learned the art of planting as a boy on the farm. It’s like riding a bike: you never forget how.

What I never learned is the art of love. Never had enough of it in my life to know. Mom Sunny run all her love through Jesus. Maybe believed he’d love her kids for her. I hardly got to know my wife Connie well enough to know if we loved each other before I went off to Afghanistan. We had good sex. That’s about it. I already guessed back then there’s more to love than sex. Calamity taught me about love from the get go. Sure, we had plenty of sex. Couldn’t wear it out. That whet my appetite for something more. I wanted total orgasm: body and soul. She laughed when I told her. “You goof. Don’t be greedy.”

She found some hydrogen peroxide in a cupboard and poured it on the gash in my hand. It erupted in a foam of bubbles. A week later she said, “I’m going to have to sew it up. It’s infected.” Found needle and thread somewheres and a ruler for me to bite down on, gripped her bottom lip with her teeth, and pulled the wound together stitch by stitch, wincing each time she pushed the needle through my skin, so I knew she never sewn up a wound before. That seemed like love to me. Still, the infection got in my blood. I was bed sick for days. She fretted and cooed over me and kept a damp rag on my forehead. I was drenched with sweat, heat coming from both inside and out.

We spent two weeks together on the ninth floor until my fever broke. I told her I’m a survivor. “I can provide for the both of us.”

“I don’t need providing for.” She frowned a little with her mouth, but her eyes smiled.

“Aren’t you the eager one One-armed and ready!”

“One’s all I need. Together, we’d have three hands between us. Should be plenty.”

“You keep saying ‘us.’ Since when are we a couple?”

“Since I’m hoping we are. Life gets lonely. I ain’t been coupled since before the war.”

She appeared to take this under advisement. Didn’t say no, anyways.

We was hungry to get out after weeks of sheltering, dangerous as it was below. I carried her down the cable on my back. People hung out in the evening cool (maybe ninety degrees out), refugees and survivors separated off in small groups. Prepared to clear out if a Stalker crew or the Night Patrol come close. Had posted guards like a colony of prairie dogs. We returned to my third floor pad on Fourth Street to see what remained to salvage. Calamity didn’t want to go—you couldn’t blame her—and said I was a fool to go back there. Seeing I was determined, she wrapped her legs around my belly and arms around my neck, and I climbed. Piece of cake. Only three stories instead of nine.

Place was trashed. Food, water and tools gone, but not my vitamins or clothes. Worst of all, the bastard took the folder where I keep my discharge papers and purple heart, wedding and birth certificates, letters Connie wrote me when I was in Afghanistan, 4-H Club certificate I got for raising a prize hog on the Kirby Farm, another I got in high school saying I was Oregon state wrestling champ in my weight class. All I had left to prove who I was. Now it was gone. Couldn’t imagine why the captain took it. Maybe wanted to erase me for taking his woman.

We heard noises in a back room. I grabbed the baseball bat I kept under my bed. We found a man lying in a pool of his own vomit, tossing and moaning in the deep shadows of the windowless room. A little blood trickled from his lips in the penlight beam. I grabbed Calamity’s arm. “Keep back. Could be Ebola or Mink16.” She shook her head, and I saw the empty bottle of Arthrinol beside him. Damn fool. Acetaminophen will kill you in large doses. Maybe wanted to kill himself. Or thought it would get him high.

“It’s J.D,” she said. “He runs with Rusty.”

She held the bottle of water we’d brought to his lips. He managed to swallow some; the rest dribbled down his chin. Poor bastard was a goner. Eyes sunk in their sockets. She moaned and run a hand back through his hair. Didn’t matter to her he was mean as a snake and once had his way with her any way he wanted. I saw right then it was more than physical beauty attracted people to her. Attracted me. Goodness shown out of her. She glowed with it, like a glaze of gold leaf covered her skin. No greater or rarer gift you could have in our cruel times than kindness—not fearlessness or the fear you inspire in others. Block captains and their enforcers, likely even Scalpers, saw it right off and didn’t know how to deal with it. Because evil fears goodness. She swabbed his brow with a damp rag like she’d swabbed mine.

“I’m done for,” he whispered. She made cooing sounds like you might to a baby.

“Where’s Rusty?” I asked and set that bat down on the floor, seeing I wouldn’t need it.

“Rusty’s right here,” a voice said from the shadows. Scared the living b’jesus out of us.

We hadn’t seen him in the darkness. “Whazzup, Pop? You missed our appointment.”

“I don’t live here no more. I got out, like you said.”

“You did live here. You still owe me for it, old man.”

He stepped into the meager light coming through the open door. In that haunted light, I recognized his features. Maybe from a dream. Or old photo I seen somewhere. Like the old-time photo I grew up with, hung over the fireplace mantel back on the family farm in Coburg, Oregon. Like a shrine: Great-Great-Great-Grandfather Homer, who founded the Kirby farm in the late nineteenth century. Family patriarch. Shave off the whiskers and remove Homer’s tattered hat, Rusty was his spitting image. High cheek bones and the grim set of his mouth. Ghostly light formed a glaze over his eyes, like in Grandpa Homer’s eyes in that photo.

“Seems like you never live anywhere long, Pop. Don’t keep your appointments either. Like the one Mother made to pick you up at the airport when you arrived home from Afghanistan. She was aching to see you even without an arm and introduce you to your baby boy. That would be me. It broke her heart when you didn’t show up. I heard about it most every day as a kid. How she decided no man would want her since you didn’t. It hurt me, too, knowing my old man didn’t have any use for me. You know what that does to a boy? You don’t really give a damn do you, you sonuvabitch?”

I stared at him, dumbstruck. He couldn’t be my son. Impossible. What was the odds of us meeting by chance on the same block in Los Angeles forty-three years after he was born?

“You spun together a story from my documents,” I said. “But I can’t figure why you want to

claim me for a father.”

“You know what, Pop, I’ve hated you so long I’ve about worn it out. I don’t feel a thing anymore but a dose of anger. You died to me a long time ago.”

Calamity looked back and forth between us, bewildered. Who could believe us meeting like this out of the blue, a father and son who’d never seen each other before?

“I’m telling you, you ain’t my son. That’s way out there past coincidence into loony

land.”

“That’s what I thought. What are the odds? I got to wondering when you said you lost your arm in Afghanistan before I found your file. There can’t be another Peter Kirby with a wife named Connie who left for Afghanistan four months before his son Rusty was born and never came back, who was raised on a farm in Coburg, Oregon and was state wrestling champ.”

“Like I said, all that come from my file.”

“Some of it. Some I already knew from my mother. But it doesn’t say in your file that you have a brother named Jerry and two sisters, Laney and Aunt Maggie, who I met once, plus my cousins Kennedy and Dugan. I never met my Grandma Sunny.”

So maybe the fascist punk was my son. Little as I wanted to believe it. “So how’s it happen we both end up on the same block in Los Angeles at the same time?”

He shrugged. “No saying. Shit happens. Both of us needy, both mean enough to stay alive, both after the same woman. The apple never falls far from the tree. Fate has had plenty of time to work it out. Tell you what, I won’t kill you for ripping me off, Pop, since we’re blood kin. I’ll honor that. But I’m going to need a foot for the grief you brought my mother.”

“Need a foot? What do you mean, you’ll need a foot?”

“Precisely that. I’ll take your right foot to balance you out.” He grinned.

“You want to cut off my right foot?” I could see he was dead serious.

“I’ll want Calamity back, too, then I’ll let you go. But if I ever see you again I’ll finish the job.” He brought what looked like a meat cleaver from behind his back. I stared in disbelief. Maybe he planned to end J. D.’s suffering with it.

“Calamity will decide what she does,” I said straight out. Preferring he kill me outright

to taking off my foot and letting me die slow.

“Put your foot up on the chair, Pop.”

There was a blur of movement to my right as he raised the blade. Calamity slammed him with the baseball bat. Hit him again as he went down. Back of his head. Sounded like the hollow thud of a foot kicking a soccer ball. I thought to drag his body to the elevator shaft and drop him down. Finish the job if he wasn’t already dead. But didn’t. He was my son, after all, though not one I’d wish for. Mean as he was, he’d likely survive. The mean ones always do.

We fled to the door opening onto the elevator shaft. Calamity leapt onto my back and wrapped her legs around my waist. I went down that cable like a fireman sliding down a pole in a long-ago firehouse. Then we run out into blazing sunlight.

____

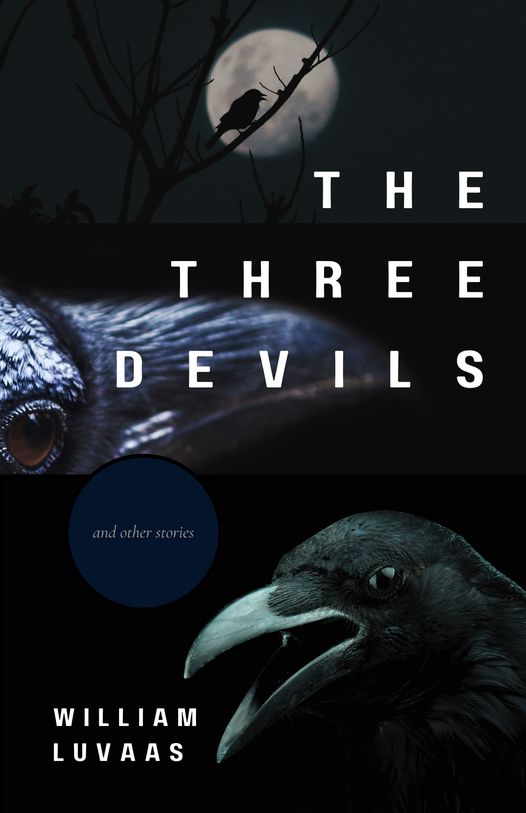

William Luvaas has published four novels and three story collections. Ashes Rain Down: A Story Cycle was The Huffington Post’s 2013 Book of the Year and a finalist for the Next Generation Indie Book Awards. His new novel Last Chance Highway is forthcoming from Spuyten Duyvil Press in 2026. His honors include an NEA fellowship and first place in Glimmer Train’s Fiction Open Contest. Over one hundred of his stories, essays, and articles have appeared in many publications, including The Sun, North American Review, Epiphany, The Village Voice, The American Literary Review, Cimarron Review, Antioch Review, Short Story, and the American Fiction anthology. “Peter’s Story” is similar to stories in his new collection, The Three Devils & Other Stories, which are mostly set in L.A. in the near future. Available on Amazon, Powell’s Books and most places books are sold.