Can we agree that professional licensing requirements are meant to be exclusionary? Whatever opportunity there was, that door is being closed.

Can we also agree that the government doesn’t create anything? Every penny they spend on this or that is a tax. Some taxes fund the civic virtues, schools, hospitals, entitlements, a bunch of good, albeit bloated and wasteful, things.

Do I need a driver’s license? I am paying a fee for…what?

That’s a thorny example. I have heard persuasive arguments that Drivers iIcenses are just to stir up more money to the Government, that they don’t cure drunk drivers, stop accidents and all the other things that can go wrong. Conversely I have been, at least temporarily, convinced that it sets a bare minimum and by doing that, screens out the most likely problem drivers.

But what of professional licenses, certifications, fees and instructions?

In the 1950s, only one in 20 U.S. workers needed the government’s permission to work within their occupation. Today it’s almost one in three.

66 occupations have greater average licensure burdens than emergency medical technicians. The average cosmetologist spends 372 days in training; the average EMT only 33.

Intrusive regulations, licensing and extraordinary bureaucracy and irrationalities are not a civic virtue, rather it is a lobbied effort to suppress competition, keeping a high barrier to entry for those aspiring to these occupations—minorities, those of lesser means and those with less education. Industry associations benefit by preserving an artificial scarcity, local government collects fees for licensing. It’s a win, win, lose

The licensing of lower-income occupations is irrational and arbitrary. If a license is required to protect the public health and safety, one would expect state by state consistency. For example, only five states require licenses for shampooers, but it is highly unlikely that conditions in those five states are any different from those in the 45 states and District of Columbia where shampooers are not licensed.

Forcing would-be workers to take unnecessary classes, engage in lengthy apprenticeships, pass irrelevant exams or clear other needless hurdles does nothing to ensure the public’s safety. It simply protects those already in the field from competition by keeping out newcomers.

Let consumers decide for themselves

Let’s do some case studies, two States:

In Nevada 31 percent of the workforce must have licensure in order to work

It is a criminal offense to practice music therapy without a license

Barbers must endure 890 days of education and apprenticeship, pass four exams and pay $140 in fees. And, Nevada does not offer reciprocity for licenses obtained in other states

For the most discerning and litigious client, Nevada’s licensing of interior designers requires payment of a $250 fee and six years of education or experience. The American Society of Interior Designers aggressively argued to State legislatures the threat to public health and safety from unlicensed interior design.

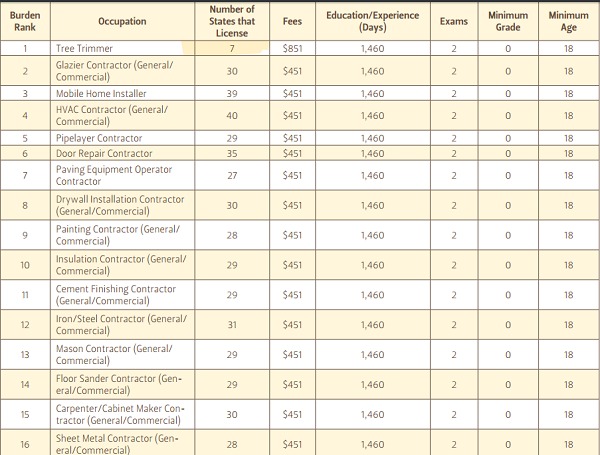

I have done forensics on California, the second most broadly and onerously licensed state in the country. The state requires a license to work in 62 of the low and moderate-income occupations. On average applicants to licensed occupations can expect to pay $300, lose 549 days to education and experience requirements and pass one exam. Why does a tree trimmer need a license, or a landscaper, dietetic technicians, psychiatric aides, still machine setters, funeral attendants, dental assistants and farm labor contractors. Why do mobile home installers need 1,460 training days to work in California when the national average for the occupation is 245.

“If they [aspiring florists] can’t take the instruction and pass the exam, how can they do an arrangement that you and I want to buy?” – Head of the state horticulture commission of Louisiana

15Mar

1000 cuts. Gig Economy, Entrepreneur & Gov licensing