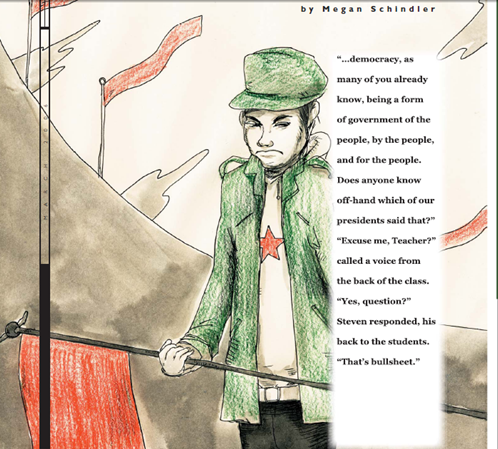

An Excerpt from Israel’s Homecoming

By: Megan Schindler

Letting his hand drop slowly to the chalk tray, Steven—ESL teacher, Ohian in his 50s, with thick blond hair and a beard he never trimmed—turned to face the class. “Who said that?” he asked. As if he couldn’t tell by the accent. The students shifted and giggled. For a moment, he thought the Mexican—India, or Israel, Iceland, whatever his name was—wouldn’t have the guts to speak up. The kid was probably scared of him. All the illegals were.

“Me,” Israel said suddenly, breaking in on Steven’s thoughts. “No.” With a flourish, the boy flipped his hair back into a pony tail, exposing his perfectly sculpted face. “I’m here,” he went on, “because they say I have to be here.”He was disgustingly handsome, Steven thought—high cheekbones, full lips, large eyes.If they weren’t so full of scorn, they would be quite expressive. “Who?” he asked. “Who says you have to be here?” “The people in the office.”

The boy’s classmates tittered again. Steven looked around the room, thinking of how much students had changed since he began his career. He’d started out as a seventh-grade English teacher in Tibalt, Ohio, a place where students had to walk two miles through corn fields to come to school. But they came. And when the first foreign student appeared—a Korean, the son of a man who’d been transferred to Cincinnati for business—he’d outdone all the others with hard work and integrity. Steven had pitied him. It was easy to care for students who wanted to learn. Now, though—now he got this.“All right, Israel,” he said. “So the people in the office told you it was necessary to take ESL 5A. Right?”

The kid nodded. “Well, fortunately for you, there are several other 5A classes for you to disrupt. I’m going to have to ask you to leave mine.”

“You can’t do that.”

“I am in charge of this class,” Steven retorted, “and I do not have to accept students spouting profanities at me.”

“But thees ees a democracy.” The class exploded into laughter. Israel enjoyed their reaction. Lips c u r l e d into a mocking smile, the boy waited smugly for Steven to respond.

What should he do? Should he rise to the bait, show Israel how foolish he was? Or should he just throw him out? Surely he had a right to do so; the kid had reduced the class to a shouting arena, raucous as a TV talk show.

But no. Steven was bigger than that. “Very good, Israel,” he responded. “This is a democracy. You do have the freedom of speech, because the founders of this nation had the foresight to provide it for you. However,” h e w e n t on, “I find it ironic that you attack our nation using the very weapons that we have given you.” Israel shrugged. “You didn’t have to give them to me.”

“Excellent place for a grammar lesson. Students,” he said, turning back to the board, “Israel just said, ‘You didn’t have to give them to me.’ What I believe he meant was, ‘You shouldn’t have given them to me.’ Can anyone explain the difference between these two statements?”

One of the Thai students raised her hand. In barely comprehensible English, she tried to answer Steven’s question. The teacher had to ask her to repeat herself several times before he could understand her. Meanwhile, he watched Israel seethe and bubble with impatience out of the corner of his eye.