“Fintech, Regulatory Arbitrage, and the Rise of Shadow Banks” is an interesting new paper by Greg Buchak, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, and Amit Seru

1. Shadow banks and fintech have grown a lot.

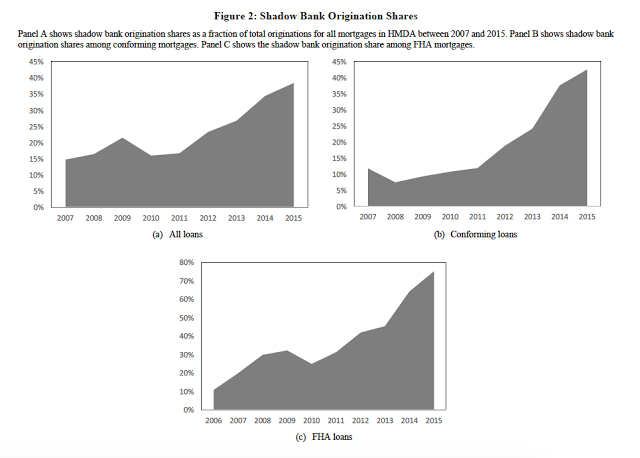

the market share of shadow banks in the mortgage market has nearly tripled from 14% to 38% from 2007-2015. In the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) mortgage market, which serves less creditworthy borrowers, the market share of shadow banks increased…from 20% to 75% of the market. In the mortgage market, “fintech” lenders, have increased their market share from about 5% to 15% in conforming mortgages and to 20% in FHA mortgages during the same period

2. Where are they expanding? They seem to be doing particularly well in serving lower income borrowers — FHA loans. They also can charge higher rates than conventional lenders, apparently a premium for convenience of not having to sit in the bank for hours and fill out forms,

Consider Quicken Loans, which has grown to the third largest mortgage lender in 2015. The Quicken “Rocket Mortgage” application is done mostly online, resulting in substantial labor and office space savings for Quicken Loans. The “Push Button. Get Mortgage” approach is also more convenient and faster for internet savvy consumers….

Among the borrowers most likely to value convenience, fintech lenders command an interest rate premium for their services.

They also specialize in refinancing

Sector shadow banks have gained larger market shares in the refinancing market relative to financing house purchases directly. One possible reason for this segmentation is that traditional banks are also substantially more likely to hold loans on their own balance sheet than shadow banks. Approximately one fourth of traditional banks loans in HMDA are held on their own balance sheet. For shadow banks, the share is closer to 5%. Because refinancing loans held on the balance sheet cuts directly into a bank’s profit, their incentives to refinance are smaller..

This is a really cool point.

Our mortgage system is based on a rather crazy product, the fixed rate mortgage with a costly option to refinance. No other country does this. I know a lot of finance professors, and none of them can tell you the optimal refinancing rule. (It takes a statistical model of the term structure of interest rates and a complicated numerically solved dynamic program.) A lot of the system seems to be price discrimination by pointless complexity, a disease that permeates contemporary America.

Banks are on the other end of this. The bank holding your mortgage doesn’t want you to refinance — it wants you to keep paying the higher interest rate. Unless, that is, it can get you to refinance too early and charge a lot of fees for it. The natural product would be a automatically refinancing mortgage, in which a computer program automatically gives you a lower rate when it’s time. It’s not hard to figure out why banks don’t offer that. In a competitive market, then, a third company would come in and offer refinancing, forcing the banks’ hands. Competition is always the best consumer protection. And that seems to be exactly what we’re seeing here.

3. Forces. A really good part of the paper (take notice economics PhD students) is how it teases out casual effects. I won’t cover that in detail to keep the post from growing too long. A paper is not about its “findings” in the abstract, but the facts and logic in the paper. Some hints of the evidence follow.

To what extent are shadow banks and fintech stepping in to fill regulatory constraints, and to what extent is it just technology?

a) Some is technology, seen by this comparison.

Fintech lenders, for which the origination process takes place nearly entirely online… By comparing .. fintech and non-fintech shadow banks, we compare lenders who face similar regulatory regimes, thus isolating the role of technology. First, we find some evidence that fintech lenders appear to use different models (and possibly data) to set interest rates. Second, the ease of online origination appears to allow fintech lenders to charge higher rates, particularly among the lowest-risk, and presumably least price sensitive and most time sensitive borrowers.

b) The shadow banks primarily originate and then sell loans, and that business is practically all through government agencies these days. Private securitization fell off the cliff in 2008 and has not come back.

In their current state, fintech lenders are tightly tethered to the ongoing operation of GSEs and the FHA as a source of capital. While fintech lenders may bring better services and pricing to the residential lending market, they appear to be intimately reliant on the political economy surrounding implicit and explicit government guarantees. How changes in political environment impacts the interaction between various lenders remains an area of future research.

In an otherwise cautious paper, I think this goes much too far. If a private securitization market existed, as it did before 2008, could shadow banks sell to them? Is the demise of private securitization just because the government killed it with the taxpayer subsidy implied by government guarantees? Absent guarantees would we just have a private industry that costs 20 basis points more? Just because finch now sells to government-guaranteed securitizers does not mean it must sell that way.

c) But the elephant in the room — are shadow banks filling in where regulations keep transitional banks from going?

Unlike shadow banks, traditional banks are deposit taking institutions, and are thus subject to capital requirements, which do not bind shadow banks. If capital requirements are the constraint that increases the cost of extending mortgages for traditional banks, we should see larger entry of shadow banks in places in which capital requirement constraints are more binding. Indeed, we find a larger growth of shadow banks in counties in which capital constraints have tightened more in the last decade

In case you missed the point,

By comparing the lending patterns and growth of shadow bank lenders, we demonstrate shadow bank lenders expand among borrower segments and geographical areas in which regulatory burdens have made lending more difficult for traditional, deposit-taking banks.

“..the additional regulatory burden faced by banks opened a gap that was filled by shadow banks. “

We argue that shadow bank lenders possess regulatory advantages that have contributed to this growth. First, shadow bank lenders’ growth has been most dramatic among the high-risk, low-creditworthiness FHA borrower segment, as well as among low-income and high-minority areas, making loans that traditional banks may be unable hold on constrained and highly monitored balance sheets. Second, there has been significant geographical heterogeneity in bank capital ratios, regulator enforcement actions, and lawsuits arising from mortgage lending during the financial crisis, and we show that shadow banks are significantly more likely to enter in those markets where banks have faced the most regulatory constraints.

4. Policy

The paper is very careful not to make policy implications. I am under no such limitation.

It is too easy to take the last point and conclude “Regulations are hurting the banks! Get rid of them so banks can get their business back!” But that does not follow (which is a good reason the paper does not say it!)

Banks have capital and risk regulations because they fund their activities with deposits and short term debt. Those liabilities are prone to runs and financial crises. So in fact, one can come to quite the opposite conclusion:The rise of fintech proves that there is no essential economic tie between loan origination and deposits or other short-term financing

(Italicized because this is an important point at the end of a long post.) Maybe we want the crisis-prone traditional banking model to die out where it is not needed!

Update: Pedro Gete and Michael Rehr also find government-sponsored securitization helps the rise of fin-tech.