Paul Krugman presents “Robot Geometry” based on Ryan Avent‘s “Productivity Paradox”. It’s more-or-less the skill-biased technological change hypothesis, repackaged. Technology makes workers more productive, which reduces demand for workers, as their effective supply increases. Workers still need to work, with a bad safety net, so they end up moving to low-productivity sectors with lower wages. Meanwhile, the low wages in these sectors makes it inefficient to invest in new technology.

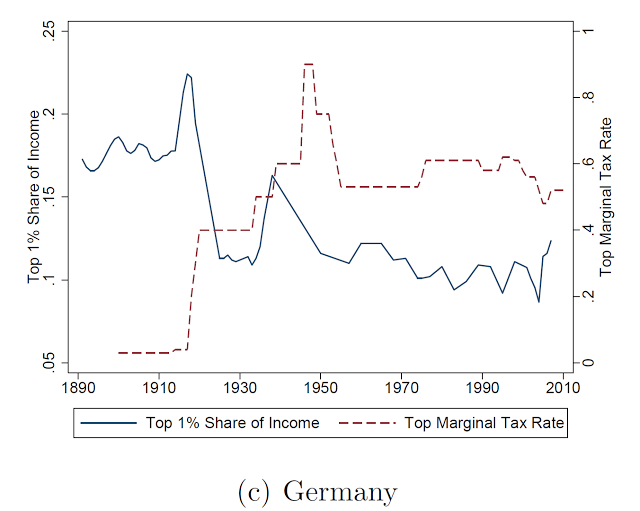

My question: Are Reagan-Thatcher countries the only ones with robots? My image, perhaps it is wrong, is that plenty of robots operate in Japan and Germany too, and both countries are roughly just as technologically advanced as the US. But Japan and Germany haven’t seen the same increase in inequality as the US and other Anglo countries after 1980 (graphs below). What can explain the dramatic differences in inequality across countries? Fairly blunt changes in labor market institutions, that’s what. This is documented in the Temin/Levy “Treaty of Detroit” paper and the oddly ignored series of papers by Piketty, Saez and coauthors which argues that changes in top marginal tax rates can largely explain the evolution of the Top 1% share of income across countries. (Actually, it goes back further — people who work in Public Economics had “always” known that pre-tax income is sensitive to tax rates…) They also show that the story of inequality is really a story of incomes at the very top — changes in other parts of the income distribution are far less dramatic. This evidence also is not suggestive of a story in which inequality is about the returns to skills, or computer usage, or the rise of trade with China.

There is a long history of constructing mathematical models to show how international trade or skill-biased technological change can influence the wage distribution in theory. However, it’s not clear to me this literature has been very successful empirically, in the end. It seems to me that any theory meant to apply to all countries will be a theory that doesn’t apply to any country. And somehow it always seems that the contributors to this literature are not aware that there is already a perfectly good explanation for rising inequality that has explanatory power internationally (and out-of-sample).

Let’s not forget that the Fed has raised interest rates 3 times already since the Taper, despite below-target inflation and slow wage growth. The labor market has been bad since 2007 (or, in fact, since 2000 — see my longer explanation here). Wages tend to grow slowly in bad labor markets, and tight money will keep them from growing quickly. There’s no need here to draw parallelograms.

21Mar

Robots v. Inequality