Amazon gotta be Amazon’ing

Many companies use tax havens, or impossible but true tax arbitrage schemes to underpay taxes to the country where it should be owed. What sets Amazon apart is that their whole business model is built around using tax avoidance as a way to help make their prices among the cheapest online.

Let’s do the forensics on two different political and taxing systems with two wildly different outcomes. It’s a Rashomon of the same tax event but seen by two different authorities. The UK/EU v United States…

Amazon U.K. services is the company’s warehouse and logistics operation in the U.K. It paid just $19.5 million in tax on European revenues of $25.5 billion dollars, reported through Luxembourg in 2016 (I converted euros to dollars to keep it easy)

It’s a nifty trick you don’t get to do at home. Amazon shoppers would make purchases in the UK and on the UK site, but…all of those internet transactions were booked in Luxembourg. In 2015 Amazon said that the practice would change: “[We are] now recording retail sales made to customers in the UK through the UK branch. Previously, these sales were recorded in Luxembourg”.

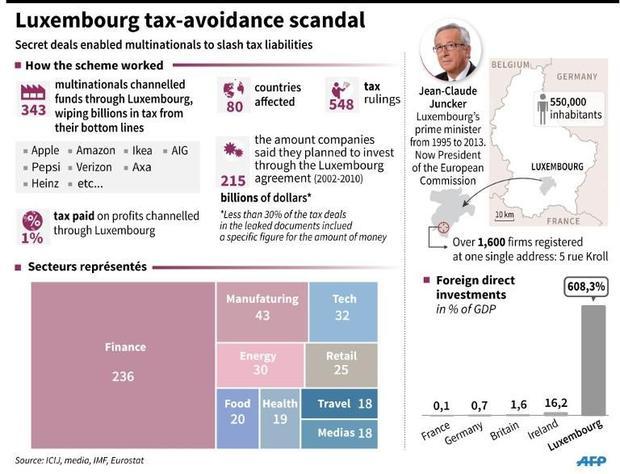

After a decade of taxable magic, the too favorable to be legal, Luxembourg tax scheme was discovered after it had been leaked. This spawned several investigations in the U.K where large amounts of taxes had been avoided, and in the EU which also was adversely affected.

In 2013 Amazon UK paid just $6.2m in tax, despite selling goods worth $6.7bn, this is more than the UK sales of Argos, Dixons or the non-food arm of Marks & Spencer, other very large retailers. The $6.2m in tax paid was just 0.1% of Amazon’s UK revenues in 2013. Luxembourg’s taxing authority set corporation tax as a percentage of profits. Amazon is able to pay low tax because when shoppers in Europe buy from any of its local websites, the payment is taken by a subsidiary based in the low tax jurisdiction of Luxembourg. A British shopper’s bank statement will show a payment to Amazon EU S.à.r.l. rather than Amazon.co.uk.

It took three years from the time the ‘kinda’ theft was found out to force a change – and that was only because of then-chancellor George Osborne’s ‘Google Tax’.

What is this thing you speak of? A Google tax…

Effective after 1 April 2015, the Google Tax is a levy on company profits, excluding those of small and medium-sized enterprises, that are routed via “contrived arrangements” to tax havens. The arrangements can concern either those that involve entities or transactions lacking economic substance, or efforts by a non-UK company to avoid a UK taxable presence.

The UK tax is set at 25% of taxable diverted profits (or 55% with respect to ring fence profits), and will raise about $450m annually by 2017/18, according to estimates.

The European Commission said that its “preliminary view is that the tax ruling… by Luxembourg in favour of Amazon constitutes state aid.” In the commission’s view, Luxembourg deviated from international standards by offering Amazon a cap on the amount of corporation tax it would need to pay in any given year. This cap was less than 1 per cent — approximately $100m in 2013 on operating company turnover of around $17.6bn. The ruling regarded payments of royalties from one of Amazon’s Luxembourg subsidiaries to another of the company’s Luxembourg subsidiaries.

The Commission found that Luxembourg did not properly look into Amazon’s “transfer pricing” proposals (how royalty payments would be moved between different Amazon subsidiaries) and whether the country properly assessed the proposed tax regime. According to the document released by the European Commission, Amazon gave Luxembourg no explanation of the intellectual property for which the royalty was paid. “If the royalty is exaggerated, it would unduly reduce the tax paid by Amazon in Luxembourg by shifting profits to an untaxed entity from the perspective of corporate taxation,” the European Commission said.

In Europe the Amazon tax scheme was detoured and Amazon corrected its practice. In the U.S, where Amazon has more political influence and politicians more eager to look the other way, the US Tax Court sided with Amazon over Luxembourg transfer pricing

The US Tax Court, established by Congress, and specializing in adjudicating disputes over federal income tax, ruled in favor of Amazon over that exact same transfer pricing scheme. Had Amazon lost it would have owed $1.5bn in taxes and ‘significant tax liabilities’ in the years to come.

Same event seen by two different systems.

Initially, before being tossed by the US Tax Court, the IRS assessed that Amazon had liabilities to federal income taxes of nearly $8.4m for 2005 and over $225.6m for 2006, arguing it did not agree with how the world’s largest online retailer has accounted for intangible assets it required to run its European arm.

Between 2005 and 2006, Amazon transferred intangible assets including software and technology used to run its European websites and fulfillment centers; marketing materials including domain names and trademarks; and customer lists to its Luxembourg subsidiary.

Between 2008-2012 Amazon paid an effective tax rate of just 9% on a total of $3,367 million of US profit. The US tax rate is 35%. In 2008-10, despite making a profit of $1,831.5 million, their effective tax rate for the period was 7.9%.

As a result, the IRS made transfer pricing readjustments, allocating income from Amazon’s Luxembourg subsidiary to the US parent business.

Amazon disputed the IRS’s methodology, arguing it treated the assets as if they held perpetual lifespans and that the IRS was including the value of intangible property that was subsequently developed. Same argument that Amazon made to Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs in th UK and in their arguments with the EU commission.

Judge Albert Lauber rejected the IRS’s case, branding it ‘arbitrary, capricious and… unreasonable’.

Cos you know, taxes are like that…