Òscar Jordà, Björn Richter, Moritz Schularick, and Alan Taylor wrote a provocative What has bank capital ever done for us? at VoxEu, advertising the underlying paper Bank Capital Redux (NBER, CEPR link here, google if you can’t access either of those)

It starts with a blast:

“Higher capital ratios are unlikely to prevent a financial crisis.”

Wow! How do they reach this dramatic conclusion? The post and underlying paper are empirical, collecting a very useful dataset on bank structure across countries and a long period of time. They show, for example, that

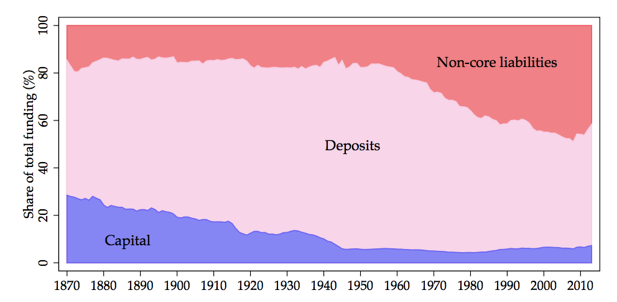

bank leverage rose dramatically between 1870 and the second half of the 20th century. In our sample, the average country’s capital ratio decreased from around 30% capital-to-assets to less than 10% in the post-WW2 period (as shown in Figure 1 below) before fluctuating in a range between 5% and 10% in the past decades.

Here is the very nice Figure 1. (It shows not just how capital has declined, but how reliance on more run-prone wholesale funding has increased. The fact that capital used to be 30% is one that we need to reiterate over and over again to the crowd that says 30% capital would bring the world to an end.)

With the facts and regressions,

We find that the capital ratio provides virtually no information about the probability of a systemic financial crisis.

Whether used singly or along with credit, higher capital ratios are associated, if anything, with a higher probability of a crisis.

There used to be a lot more capital, and there used to be a lot more financial crises.

Wow. Now, (this is a good quiz question for a class), before you click the “more” button: Do the facts justify the conclusion? And if not why not?

Well, obviously not, or at least not yet. Ask the standard questions of any correlation or forecast in economics: 1) Does it reflect reverse causality — rich guys drive Mercedes, but driving a Mercedes will not make you rich? 2) What causes the movements in the right hand variable (capital)? They are not random experiments, whims of the God of financial regulation. 3) What other causes of crisis are there (the error term)? Why are they not correlated with the right hand variable (capital?).

The opportunities for reverse causality are rich — and fully acknowledged. Continuing the above quote:

“… higher capital ratios are associated, if anything, with a higher probability of a crisis. This mechanism is consistent with banks raising capital in response to higher-risk lending choices, rather than as a buffer against a potential systemic crisis event in the economy….”

The paper is even clearer:

“…Such a finding is consistent with a reverse causality mechanism: the more risks the banking sector takes, the more markets and regulators are going to demand banks to hold higher buffers.”

It is not surprising that more fire extinguishers predicts either nothing, or more houses burning down. People buy fire extinguishers in fire-prone areas. It is not surprising that airplanes in which pilots wear parachutes are more likely to crash than when pilots don’t wear parachutes. It would be an obvious mistake to conclude that buying fire extinguishers and wearing parachutes do not increase house or pilot safety.

Similarly, it is not at all surprising that banks, their depositors, their equity holders, and their regulators all would choose more capital when the chances of a crisis are greater. It is not at all surprising that the probability of a crisis in equilibrium is independent of the amount of capital chosen — the supply of capital just balances the dangers of crisis. All of this is not at all surprising if adding more capital at any point in time would further reduce the probability of a crisis.

Other effects are just as important. The probability of a crisis also depends on deposit insurance, topnotch risk regulators out there spotting impending crises (hmm), bailouts, and so on. We have arguably traded less capital for more of these other responses — inefficient, in my view, full of moral hazard, but effective in putting out fires — so no wonder less capital comes with less (before 2008) or no change in frequency of crisis.

Once again, the authors are completely upfront — eloquent indeed — about other effects (error terms correlated with the right hand variable)

Increasing sophistication of financial instruments allowed banks to better hedge against uncertain events. As a result, the business model of banks became safer, implying a lower need for capital buffers (Kroszner (1999), Merton (1995)). Furthermore, diversification and consolidation in banking systems may have reduced the equity buffers required to cope with risk (Saunders and Wilson (1999)).

Probably the most prominent innovation in this respect was the establishment of a public or quasi-public safety net for the financial sector. Central banks progressively took on the role of lender of last resort, allowing banks to manage short-term liquidity disruptions by borrowing from the central bank through the discount window (Calomiris et al. (2016)). The second main innovation in the 20th century regulatory landscape was the introduction of deposit insurance. Deposit insurance mitigates the risks of self-fulfilling panic-based bank runs (Diamond and Dybvig (1983)); but it may, however, also induce moral hazard if the insurance policy is not fairly priced (Merton (1974)). …

A last and arguably more recent extension of guarantees for bank creditors relates to systemically important or “too-big-to-fail” banks. While explicit deposit insurance tends to be limited in most countries to retail deposits up to a certain threshold, large banks may enjoy an implicit guarantee by taxpayers. This implicit guarantee could also help account for the observed increase in aggregate financial sector leverage, although the subsidy is difficult to quantify.

What do the authors do about this? Amazingly, nothing. The paper fully acknowledges reverse causality as a plausible, and perhaps the most plausible interpretation, it outlines a host of other effects correlated with the right hand variable — and then goes on to do nothing about it.

Regression econometrics these days is exquisitely sensitive to these issues. Paper after paper tries to isolate a “natural experiment” — an increase in capital unrelated to increased probability of crisis — or adds differences in differences in differences and a plethora of fixed effects and controls to try to measure the correct cause and effect relationship. This isn’t always successful, and throwing out 99% of the data variation is sometimes more confusing than revelatory, and sensitive to just which 99% one throws out, but give them credit for trying. This paper doesn’t even try.

Now, perhaps I have mischaracterized the “fact,” in the above graph, emphasizing the association of declining capital over time with the frequency of crises. In fact the real evidence in the paper comes from a forecasting regression across time and across countries, of crisis at time t+1 on capital and other variables at time t

So, does this capture the correlation of declining capital ratios over time with the chance of crisis? Or does it capture the correlation of different capital ratios across countries with the country’s chance of crisis? (Notice here the severity of crisis is left out, that’s the later fact.) Well, both since we have both i and t.

Alas, (p. 16)

“To soak up cross-country heterogeneity, we will include a country fixed effect αi for each of the 17 countries….”

That means they throw out the variation, do countries which on average have higher capital standards than others, on average have fewer crises? Why in the world would one throw that out? Why are cross-country capital ratios more polluted by endogenous responses than over time capital ratios, and cross country crises more contaminated by correlation with other effects — amount of mortgage market interference, lender of last resort effectiveness, deposit insurance, etc? If the time series variation is important and exogenous, why exclude the major source of variation, the pre vs. post WWII variation?

in sum, commandment #5 of regression running is: Think about the source of variation in your data. Don’t just randomly throw in country or time fixed effects or split the sample in half.

(Yes, “Pooled models are included in the appendix as well.” But that isn’t much help. )

The problem is not with the paper, which is otherwise excellent. The problem is with the paper’s headline conclusion — more capital therefore does not help to reduce the chance of a crisis.

The paper does show, and correctly claims it shows, that capital ratios (in equilibrium) are not helpful in forecasting a crisis.

“our first main finding is that, perhaps counterintuitively, the capital ratio is not a good early-warning indicator, or predictor, of systemic financial crises.”

For example, a regulator who wants to stop crises might look at banks piling on capital as a danger signal, the way passengers in my glider are sometimes suspicious when I ask them to put on a parachute. The paper verifies that capital is useless as a forecaster. That is a good, solid point. We might have expected the opposite sign — more capital, more crisis — as a useful forecast. But we cannot infer that adding more capital would not reduce the chance of a future crisis.

The paper also makes a nice point about capital, which is not just nice because I agree with it but because the data more clearly support it: More capital means the crisis, when it comes, is less severe. The wearing of parachutes may not forecast safer flights, because people tend to put them on when the flight is more dangerous anyway. But when people do wear parachutes, the outcomes of midair collisions are a lot less severe.

“a more highly levered financial sector at the start of a financial-crisis recession is associated with slower subsequent output growth and a significantly weaker cyclical recovery. Depending on whether bank capital is above or below its historical average, the differences in social output costs are economically sizable. Real GDP per capita five years after the start of the recession is about 5 percentage points higher when banks are well capitalised than when they are not. This difference is displayed in Figure 2.”

One can complain about reverse causality here too, but the point is not to whine, the point is to see if there is a really plausible channel, and the strength of the counterargument here seems less strong to me. It does not seem likely that if people knew an unusually bad recession was ahead, or that the economy was unusually sensitive to financial shocks, they would then equilibrate to less capital.

But why did the authors take a very nice paper that shows that equilibrium (including political and economic equilibrium) doesn’t forecast a crisis, and plaster on it a completely unsubstantiated conclusion that more capital would not help to reduce the probability of crisis?

At first I suspected it wasn’t their fault. Oped editors frequently pick titles without the authors’ knowledge. But it’s in the first sentence of the paper abstract.

“Higher capital ratios are unlikely to prevent a financial crisis.”

The authors say it again at the end of the oped,

the main role for bank capital appears to lie not so much in eliminating the chances of systemic financial crises, but rather in mitigating their social and economic costs – a distinct but arguably more important benefit.

(My emphasis.) And the paper repeats the point,

we find that macroprudential policy, in the form of higher capital ratios, can lower the costs of a financial crisis even if it cannot prevent it.

history does indeed lend support for a precautionary approach to capital regulation. Its main role appears to lie not so much in eliminating the chances of systemic financial crises, but rather in mitigating their social and economic costs…

Why am I making such a fuss?

First, in the sad state of current academic-media interactions, this is sure to be picked up and quoted as “A major study shows that” more capital does not help to prevent crises. (Perhaps in a week or two I’ll find time to do some google searches to verify this conjecture.) No, studies that claim a result do not always show a result! This is a classic case. Please, ask what evidence the “study” offers, and is it even vaguely logically coherent!

Second, it is a very instructive case study for students to look at — how to ruin a great paper by trying to make sexy claims that are not supported by the logic of the paper.

Third, in that vein it allows me to reiterate some important lessons about how to run regressions, lessons that we tend to forget too often.

2017/04/capital-cause-and-effect.html