Japan has managed to offset decades of deflationary dynamics, but at a cost that is hidden beneath the surface of apparent stability.

Do we implode in a deflationary death spiral (ice) or in an inflationary death spiral (fire)? Debating the question has been a popular parlor game for years, with Eric Janszen’s 1999 Ka-Poom Deflation/Inflation Theory often anchoring the discussion.

I invite everyone interested in the debate to read Janszen’s reasoning and prediction of a deflationary spiral that then triggers a monstrous inflationary response from central banks/states desperate to prop up their faltering status quo.

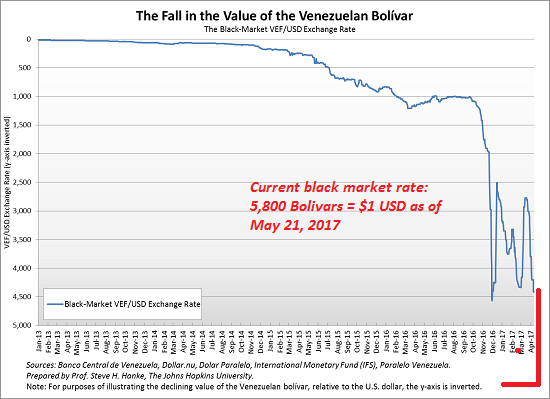

Alternatively, economies can skip the deflationary spiral and move directly to the collapse of their currency via hyper-inflation. This chart of the Venezuelan currency (Bolivar) illustrates the “skip deflation, go straight to hyper-inflation” pathway:

As populations age and retire, the resulting decline in incomes and spending are inherently deflationary: less money is earned, and less money is spent, reducing economic activity (gross domestic product).If we set aside the many financial rabbit holes of the inflation/deflation discussion, we find three dominant non-financial dynamics in play:demographics, technology and energy.

The elderly also sell assets such as stocks, bonds and their primary house to fund their retirement, and if the elderly populace is a major cohort (due to low birth rates and increasing life spans, etc.), then this mass dumping of assets is also deflationary, as the increasing supply of sellers and the stagnating supply of buyers pushes prices lower.

Recession and stagnation are also deflationary. Shift 10 million workers from secure fulltime employment with full benefits to low-paid, insecure part-time jobs with few benefits, and you have a self-reinforcing deflationary spiral in action: a significant percentage of the workforce is now receiving far less income, which necessarily slashes their spending and just as importantly, their ability to borrow huge sums of money to buy vehicles, homes, overseas vacations, etc.

In consumer-dependent economies that are dependent on debt for much of the consumer spending, this decline in borrowing and spending power is extremely deflationary, as there is a lot less money available to chase the existing output of goods and services.

Japan is a case in point. A friend of ours who lived and worked in Japan for a decade (the 1990s) recently visited Japan again after 15 years working in Europe and the U.S., and he was surprised to find prices were the same or lower as when he was living in Japan.

This is the result of multiple sources of deflation operating in Japan.

A recent NHK TV program reported some young people in Japan are trickling back to rural villages and renting large traditional farm houses and the adjoining land for $200/month, a fraction of what they were paying for cramped studios in big cities. This is an example of deflation in action: people abandon costly housing, transportation, etc. and adopt lifestyles that generate far less income and far lower expenses–both are deflationary.

Given the structural rise of part-time employment, an aging populace and the deflationary impacts of technology and globalization, no wonder Japan is experiencing deflationary/stable prices.

Technology is relentlessly deflationary. Where consumers once spent small fortunes buying stereo equipment and music storage (LPs, cassettes, CDs, etc.), cameras, film, photo printing, etc., game consoles and equipment, small-screen TVs, and paying for telephony, now a single device–a smart phone–combines all these functions (with some obvious limitations) in one device.

Globalization and commoditization are also deflationary. Global wage arbitrage and automation lowers production costs, and the commoditization of labor and inputs (capital and materials) push prices lower.

Declining energy costs are also deflationary, as the cost of energy affects the pricing of almost every good and service.

We now discern the outlines of why money created out of thin air needn’t be as inflationary as expected. If economic activity declines by $1 trillion due to lower incomes, spending, etc., creating $1 trillion out of thin air and injecting it into the economy as monetary and fiscal stimulus is more or less simply replacing the $1 trillion of deflation.

The Bank of Japan has tripled its asset purchases (monetary stimulus and support of the stock and bond markets) with little apparent effect on conventional measures of inflation.

This print-to-offset deflationary declines may appear to be stable and sustainable, but the expansion of bonds (to fund fiscal stimulus) accrues interest, which even at low rates eventually starts burdening state spending.

All this new currency doesn’t necessarily lead to productive spending or investment; rather, it may increase mal-investment and systemic asymmetries that eventually destabilize the entire financial system.

Japan has managed to offset decades of deflationary dynamics, but at a cost that is hidden beneath the surface of apparent stability. Building bridges to nowhere and creating money from thin air to buy stocks and bonds only appears sustainable because the risks and imbalances are piling up out of sight. Eventually the “perfect balance” between deflation and inflation tips one way or the other, and a systemic crisis “nobody saw coming” unfolds.